Ga Fl News

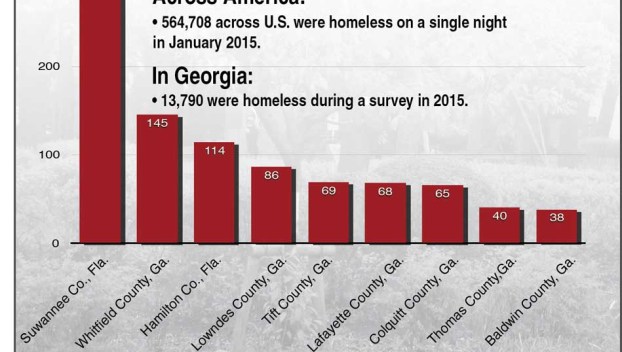

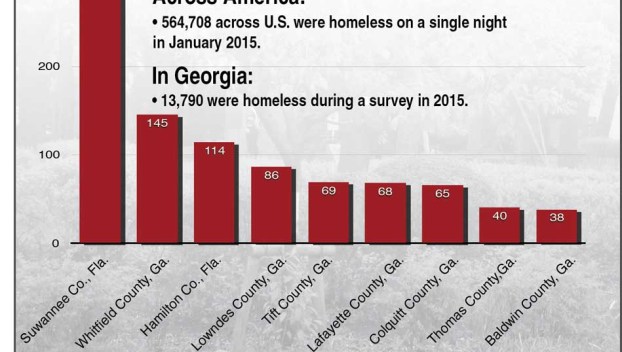

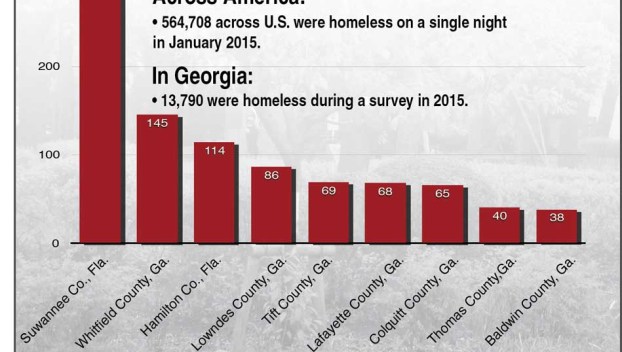

Life on the Streets: Many paths lead to homelessness

VALDOSTA — On the outside, Matthew May and Zekevis Williams could not be more different. Read more

VALDOSTA — On the outside, Matthew May and Zekevis Williams could not be more different. Read more

MOULTRIE — On the outside, Matthew May and Zekevis Williams could not be more different. Read more

TIFTON — Several convenience stores in Tifton have been victims of armed robberies over the past 10 days, ... Read more

TIFTON — An Adel man was found dead in Tifton Saturday morning, according to Tifton Police. Read more