Only one survived the sinking of SS Daniel J. Morrell 56 years ago Tuesday — the late Dennis Hale of Ashtabula

Published 12:00 am Monday, November 28, 2022

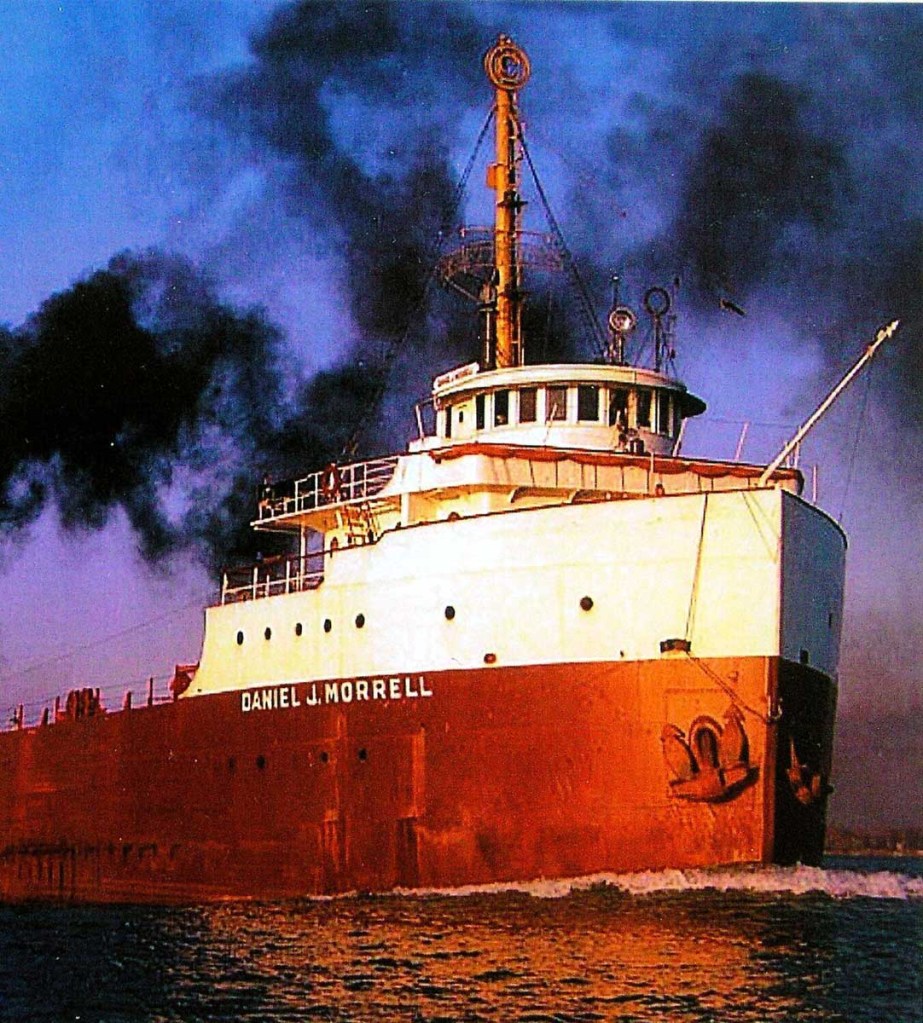

- The SS Daniel J. Morrell, a Great Lakes freighter that split in two and sank Nov. 29, 1966, killing 28 of its 29 crewmen. An Ashtabula resident, Dennis Hale, was the lone survivor.

The ill-fated ship left the Bethlehem Steel Corp. in Lackawanna, N.Y., heading toward Minnesota to pick up iron ore when it ran into a fierce storm.

The combination of 65 mph winds and 30-foot waves on frigid Lake Huron proved deadly for the SS Daniel J. Morrell, a Great Lakes freighter that split in two and sank, killing 28 of its 29 crewmen.

The sinking of the Morrell occurred on Nov. 29, 1966 — 56 years ago Tuesday.

The only survivor was the watchman, the late Dennis N. Hale, of Ashtabula.

Hale died in 2015 at age 75.

For nearly 20 years after the sinking, Hale didn’t talk about the incident because it was too painful for him.

The turning point came in 1982 when Hale spoke at the premier of a film about the shipwreck. He decided he owed the 300 people who gathered there to tell the entire story.

“When I left there, I felt like a huge weight had been lifted off me,” he said in a Star Beacon interview with former reporter Carl E. Feather in June 2009.

Hale went on to tell the story of survival to newspaper and television reporters, in speeches at libraries, museums and schools and in his autobiography, “Shipwrecked: Reflections of the Sole Survivor.”

In 1998, Hale became the curator of the Marine Museum in Ashtabula, where he frequently talked about what it was like to spend 38 hours adrift in a lifeboat during a November storm.

During Feather’s June 2009 interview, Hale said, “I want to keep the memory of the Morrell alive. I don’t want it to die, at least as long as I’m alive.”

By coincidence, the Morrell had the same number of people on board, 29, as the better-known SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank in another November storm on Lake Superior in 1975. The Fitzgerald gained more fame, thanks to the 1976 Gordon Lightfoot song about the sinking.

No one sang about the Morrell, but it’s still an amazing story of survival.

The story begins at 8 p.m. Nov. 28, 1966, when Hale, then a 26-year-old watchman, finished his four-hour shift, ate dinner and crawled into his bunk at about 9:30 p.m., according to the book “Queen of the Lakes.”

Disaster struck at 2:01 a.m. and abruptly awakened Hale even before the ship’s alarm went off.

Clad only in his underpants, Hale jumped out of bed, grabbed his life jacket and headed to the deck.

Crew mate Norman M. Bragg, of Niagara Falls, told Hale he better get more clothes on. Hale grabbed a peacoat that he put over the life jacket.

The ship had broken in two, and Hale somehow managed to jump into a raft, along with three crewmen. The four men watched as the ship’s bow sank and the stern drifted away in the dark of night.

The four shipmates huddled together against the brutal elements, for the start of what would be a 38-hour ordeal for Hale.

At about daybreak, he discovered that two of the men in the raft had died. Then that afternoon, the third man died, leaving only Hale.

Wearing only in his undershorts, life jacket and the peacoat, and sitting in a raft with three dead shipmates, Hale hung to life surrounded by 40-degree water and air temperatures around 32 degrees.

During his hundreds of speaking engagements, Hale often recounted a vision he had as he drifted in and out of consciousness on the raft.

As the hours passed, Hale became desperately hungry and thirsty. Hale was tempted to eat the ice off his coat, but an elderly man with a white beard begged him not to eat it. The ice would have lowered his body temperature further, providing him with less chance of survival.

That night, the raft bobbed near the shoreline at Harbor Beach, Mich., and Hale could see the lights come on in the homes and farms near shore. He fired off flares, but no one came.

He passed the dark night playing games in his mind, but most of the time he said he was praying. He felt himself being drawn up in the clouds, where he later told the Star Beacon, “All my worldly pain and hurt were gone. The love was so profound.”

Somehow, Hale had managed to survive and at about 4 p.m. Nov. 30, a Coast Guard helicopter rescued him. He was airlifted to Harbor Beach Community Hospital, where doctors attempted to raise his body temperature. He later learned his body temperature hovered around 92-94 degrees when he arrived at the hospital.

After spending weeks in the hospital, Hale was on his own. There was no workers compensation or unemployment checks. He sued the steamship company and won a small settlement, he told the Star Beacon in 2009.

He trained as a tool and die maker but vocational training didn’t change the fact that he was a lone survivor. He avoided going out in public because people would stare at him, he said.

The Morrell sinking has been blamed partly on its captain’s arrogance in believing his ship could get through the gale.

Investigators also later learned that the metal used in building the Morrell in 1906 was too brittle and cracked in the terrible cold weather.

Later in life, in addition to making public appearances and writing his book, Hale started his own website, greatlakessurvivordennishale.com, before he died from cancer on Sept. 2, 2015.

In many interviews throughout his life, Hale said he had “a lot of faith in God” and believed that his faith and time in prayer helped him survive the sinking of the Morrell. There were other factors, as well. Unlike the other sailors who were fully dressed, Hale was not laden with wet pants.

Growing up in Ashtabula, Hale was conditioned to handle the cold. More than a decade later, it paid off, he told the Star Beacon in 1999.

Several remembrances of the 50th anniversary were held in 2016, including a memorial service held at the Saybrook Banquet Center, sponsored by the Ashtabula Maritime and Surface Transportation Museum in Ashtabula.

“As the 50th anniversary of the Daniel J. Morrell sinking came around, we discussed with Barb [Hale] about having a bell ringing ceremony,” said Bob Frisbee, museum director. “We had museum members, family members of lost sailors aboard, and friends ring the bell in honor of each man lost.”

The bell rang for each of the 28 victims, as well as for Hale.

“It was a very sad occasion for everyone who attended,” Hale said. “I still miss Dennis Hale, the lone survivor, after all these years. He was a great friend.”

Sources: “Ships and Men of the Great Lakes” (1977, Dodd, Mead & Co.) by Dwight Boyer, Star Beacon reports from 1966, 1982, 1999, 2009, 2015 and 2016, Great Lakes & Seaway Shipping Online and the buffalonews.com