Dakota bring their language back 150 years after mass execution

Published 4:45 pm Friday, October 18, 2019

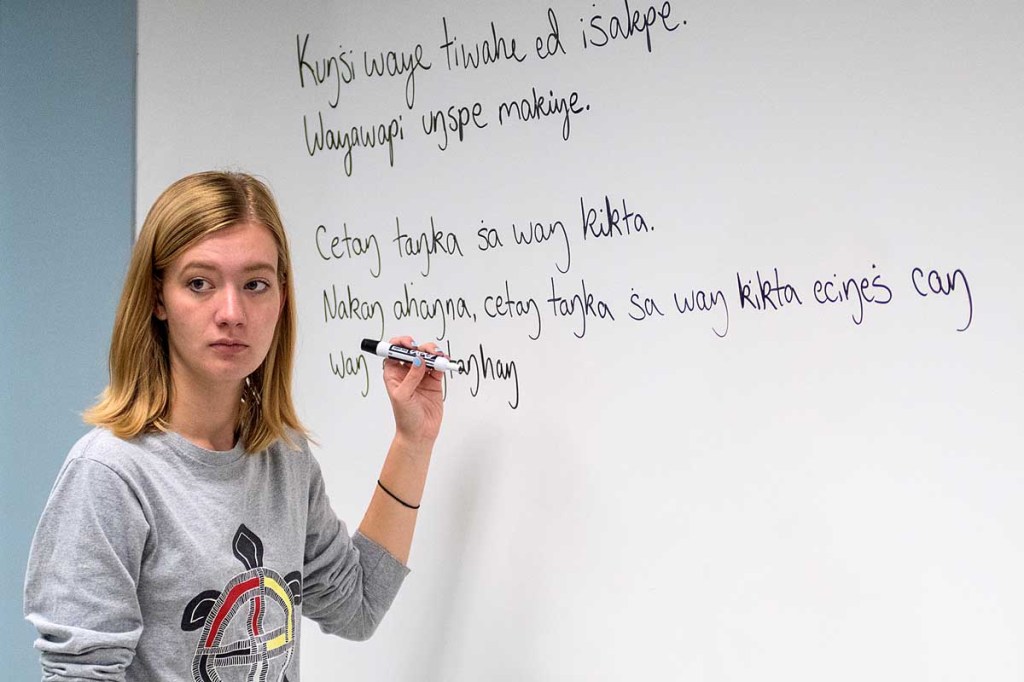

- Clare Carroll listens to a classmate while writing sentences in Dakota during class at Minnesota State University, Mankato. “I’m not native so I do get that response, why would you learn it?” said Carroll. Her answer to that is: “This school is on Dakota land, it’s out of respect and it’s the least we can do.”

Some 150 years after the mass execution of their ancestors, the Dakota have brought their language back to life in the place that tried to erase it.

The Dakota were among the indigenous peoples of southern Minnesota when white settlement, broken treaties with the U.S. government and eventually a war in 1862 forced them out. The largest mass execution in U.S. history occurred in Mankato on Dec. 26, 1862, when 38 Dakota were hanged without proper trials as a result of actions in the 1862 Dakota War.

Minnesota State University, Mankato, began offering the Dakota language course four years ago as a way to preserve “the rich and proud culture and heritage of the Dakota people in our region,” according to a statement by MSU President Richard Davenport.

Dakota language teacher Glenn Wasicuna has observed through his 20-year career how people pick up the language he was taught by his elders.

“A non-Dakota person will learn faster, a non-Dakota person sees it as just a language and there is no baggage connected to it. But for the Dakota person, it comes with baggage.

“It’s a brutal history. When you think about Dakota, and you think about all the negative events, the trauma prevents learning.”

One of the reasons Wasicuna wanted to be a professor at Minnesota State University was “to teach the teachers” about the indigenous language he speaks.

“I wanted to catch them so they know the basics of Dakota,” Wasicuna said.

He wants educators, when teaching Dakota history as a course requirement, to be properly equipped.

Language and history go hand in hand as class subjects, Wasicuna said. As his students add words to their vocabulary, they also learn lessons in Dakota culture.

“For the Dakota person, it heals them to hear about what happened. It’s a difficult journey, but at the same time it’s healing and then the language comes in after that.”

He said the best method of passing on the culture is to speak to his students, with a one-to-one approach being the most effective.

“I let them ask questions and decide what they want to learn. I don’t want them to learn the same sentence. Because when they leave here, if you asked them ‘what did they learn?’ they would all say the same thing.”

Students write their day-to-day experiences in notebooks. They also jot down questions about word usage.

“Every time they come here I want them to ask me, ‘Glenn, how do you say this in Dakota?’ If there is a need, then we will expand.”

“Is it Koda or Kota?” — was one student’s query about how to refer to a female friend.

Wasicuna discussed Dakota word gender and pronunciation, then asked if what the friend’s name was and if she was a sister or an aunt.

“It’s much nicer to name your friend or relative,” he said.

A few weeks into the semester, the small group of Dakota language students were making clear progress toward proficiency.

His students have a variety of reasons for taking the class, which meets four days a week.

Marilyn Allen wants to share the knowledge she picks up with her family. She described herself as part Dakota and Lakota.

Evelyn Brock said she’s been asked, “Why would you waste your time learning a dead language?”

“It’s not a dead language because we’re in here speaking it,” was student Clare Carroll’s counter to that comment.

“This school is on Dakota land, it’s out of respect and it’s the least we can do,” Carroll said, adding that she is not Native American.

“We live in a Native area and they learned our language, so why shouldn’t we learn theirs?” Brock said.

Native American parents are also bringing the language back and passing it on to their children.

One Mankato family is making an effort to teach an indigenous language at home. Parental advice in the Nathan and Megan Schnitker household to their kids with cold toes is to go “find your humpas (shoes).”

The couple is raising a blended family — six children who range in age from 10 years to 2 months.

With the help of a Lakota language phone app that pronounces the names of animals and common objects, their children are familiar with many Lakota words.

Megan, who learned English as her first language, said she is not fluent in Lakota, the dialect similar to Dakota she grew up hearing her elders speak.

“I’m like my Dad. We can understand it, but speaking it is harder for us.”

She said there’s an urgency in passing on Lakota words and traditions to the next generation because few elders remain who are familiar with the language.

“Our culture was ‘illegal’ until the 1970s. We are working to revive it. We want them to know who they are. And we want to keep our language and our culture and traditions alive,” she said.