Quiet Epidemic: Lowndes County suicides on the rise

Published 3:00 am Wednesday, February 20, 2019

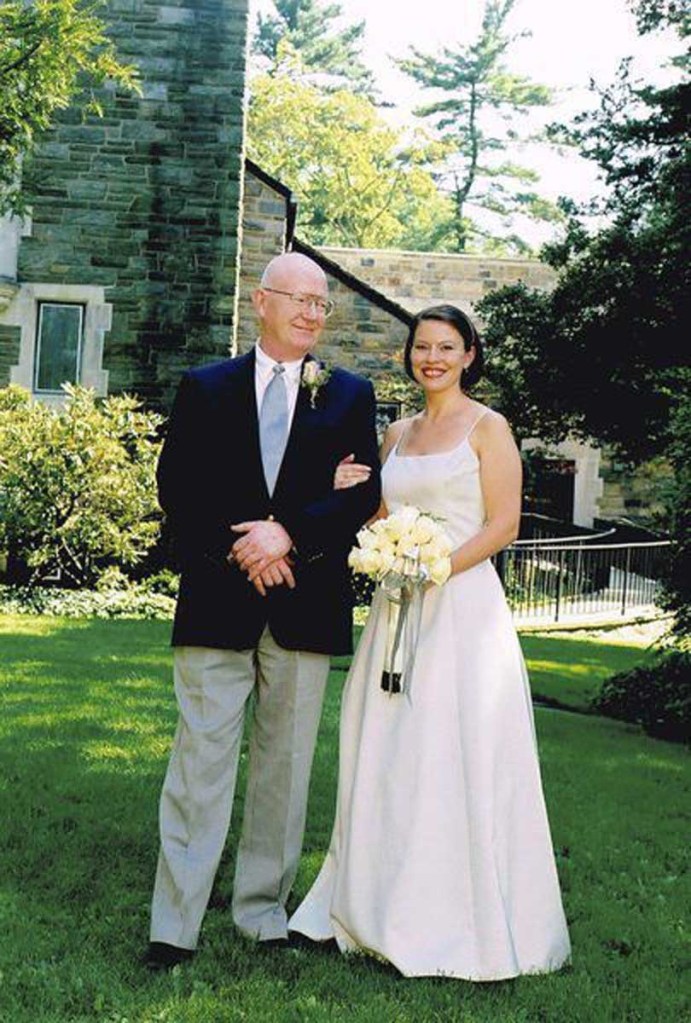

- SubmittedThomas Jefferson Hardesty and Tamara Hardesty at her wedding four years before her father died from suicide.

VALDOSTA — When Tamara Hardesty’s father died by suicide in 2004, his death was a shock, but not a surprise.

Her father struggled with bipolar disorder for decades, and as he aged, his medication stopped being effective and started producing negative side effects.

“He decided to stop taking his medications,” Hardesty said. “Within several weeks, he was angry, suicidal and put quite an elaborate plan into motion.”

When she got the call from the coroner and heard how he died, she knew right away what had happened, she said. After a full investigation into her father’s death, the coroner reported that he died “as a result of his own actions.”

Lowndes County Coroner Austin Fiveash said stories like Hardesty’s are becoming more and more common. During the past four years, suicides in the county have steadily increased.

In 2015, there were 12 suicides followed by 15 in 2016, 21 in 2017 and 30 in 2018. The victims in these situations are overwhelmingly white males who predominantly use firearms to end their lives, according to statistics provided by the coroner’s office.

“It’s definitely going up,” Fiveash said. “Most of the time it’s a gunshot wound. There has been a growing number of older people suffering from what I call ‘health care induced depressions.'”

Like Hardesty’s father, Fiveash said older people are becoming more prone to suicide from being in constant pain because they are not receiving proper treatment or because they see themselves as a burden on their family.

The bottom line, he said, is people are not receiving treatment.

Treading Water

Valdosta Police Lt. Adam Bembry said he has noticed an increase in calls related to people suffering from mental health issues and thoughts of suicide since he joined the department in 2005.

When someone threatens to take their life, the first line of defense is law enforcement.

He said when he joined the force, police received maybe one call a week. Now, it’s one call every 12-hour shift, he said.

Law enforcement is not intended to deal with suicide threats, Bembry said. The mission is to enforce the law and fight crime.

“These are mostly medical issues,” Bembry said. “Although we are trained in it to a point, we’re not counselors. We’re not psychologists. My officers are doing the best they can, but when you are dealing with the mentally ill, it is very difficult.”

He said the way the current system works is police are called to a scene where someone is considering suicide. The person is then taken to a hospital where they are held for a set amount of time and then released once they no longer pose an immediate threat to their life.

Bembry calls this a revolving door.

The person has not been treated for the underlying issue related to the disorder. He said police receive calls for the same individuals so often officers are on a first-name basis with some of them.

“Us and the ER are dealing with the same people over and over and over again,” Bembry said. “This is not a problem that can be solved in this manner.”

But the blame doesn’t fall on the person threatening suicide, he said.

“It’s not their fault. They’re sick,” Bembry said. “What is going on is not a solution at all. We’re just treading water.”

Ignored Disease

Hardesty said a societal change is needed.

Suicide is spoken of in hushed voices, she said.

She compares it to how cancer was originally considered, when people would whisper that someone had cancer. Today, however, cancer is treated like any other sickness. It is treated, fought. Organizations are created to raise awareness of the symptoms so it can be caught early.

This, Hardesty said, needs to happen with mental illness.

“I think of mental illness truly as an illness,” she said. “You can live with it. I think we have to understand that mental illness is something that can be treated, but sometimes there is an acute break with reality and there is nothing you can do that is going to prevent their suicide.”

She said she doesn’t consider the man who took his life to be her father. He wasn’t in his right mind, she said. His brain literally stopped working.

“I don’t think I would have recognized him, and I don’t think he would have recognized me,” Hardesty said. “If he were in his right mind, he would never have hurt me like this.”

When she got the call from the coroner that day more than 14 years ago, the news hit her so hard she fell to the floor.

Grieving a suicide is a roller coaster of feelings, she said.

“It has the suddenness of an accident, the anger of a murder and then just the loss of the person,” Hardesty said. “You are angry at the person for murdering themselves, and then you feel guilty for feeling angry.”

The first thing she did after going through this range of emotions was seek a support group. She was living in Connecticut at the time and found great healing in learning she wasn’t alone.

She met with people who also lost loved ones to suicide. The group helped out so much she became certified and began leading her own group.

Years later, she and her husband moved to Valdosta to work at Valdosta State University, and Hardesty noticed there wasn’t a support group in town, so she started one.

The group, however, failed to make traction and ended due to a lack of attendance. She blamed the lack of attendance not on a lack of people going through the same trauma as her but on people in the South feeling unwilling to seek help.

“People in the South don’t want to air their dirty laundry,” Hardesty said. “It’s still seen as this dirty little secret that you keep among family.”

Reaching Out

Despite the unwillingness to seek out help in Valdosta and Lowndes County, there are resources available for people on a national level.

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention is a voluntary health organization that funds research, runs educational programs, advocates for public policies in mental health and suicide prevention and supports survivors of suicide loss.

Recently, Georgia state officials announced a new mobile application to support the Georgia Crisis and Access Line, a 24/7 hotline offering free and confidential access to services for mental illness, substance use disorders and intellectual and developmental disabilities.

The app enables users to receive immediate support by communicating with caring GCAL professionals via text message, chat or phone.

While the My GCAL app is targeted at youth, GCAL is available to anyone in Georgia.

Hardesty said mental health should be treated like any other health-related issue. Anyone would seek help for any other disease. Suicide should not be treated any differently.

“You have to think about this as a disease in your brain that can be treated and not as a personality flaw,” she said. “If you’re sinking, reach out. You’re not alone.”

For help, call Georgia Crisis Line, (800) 715-4225; or National Suicide Prevention Hotline, (800) 273-TALK.

Thomas Lynn is a government and education reporter for The Valdosta Daily Times. He can be reached at (229)244-3400 ext. 1256