TAXED: Weighing the burden of property taxes

Published 3:00 am Sunday, July 9, 2017

- TAXED: Weighing the burden of millage rates

VALDOSTA — “Government in general is just a monster. … You can never fill its appetite,” Ricky Gamble said. “The more you give it, the more it will spend.”

Gamble is not a disgruntled taxpayer. He’s the County Commission chairman of Suwannee County in North Florida.

Although his words won’t often be repeated by other elected officials, Gamble’s view of government is a common one. Every time a local government introduces a tax hike, residents accuse city and county leaders of wasting money, of padding their own pockets, of overstepping their bounds.

Property taxes often loom large in these political clashes because they are a heavyweight on the tax bill.

When leaders raise the millage rate — the number used to calculate property taxes — they justify the increase by pointing to an unfavorable economy and declining sales tax revenue. They say without a certain level of taxes, they wouldn’t be able to provide the expected level of services to residents.

“Without property taxes, there would have to be significant cuts,” Valdosta Mayor John Gayle said. “Police and fire represent 65 percent of the budget and 70 percent of the personnel in the general fund, which includes property taxes.

“If we want a safe community with a good quality of life, then taxes are necessary.”

Across the SunLight Project coverage area — Valdosta, Dalton, Thomasville, Milledgeville, Tifton and Moultrie, Ga., and Live Oak, Jasper and Mayo, Fla., along with the surrounding counties — common factors drive city/county millage rates and the numbers are pretty similar, with a few outliers on each end of the spectrum.

How do millage rates stack up in the region?

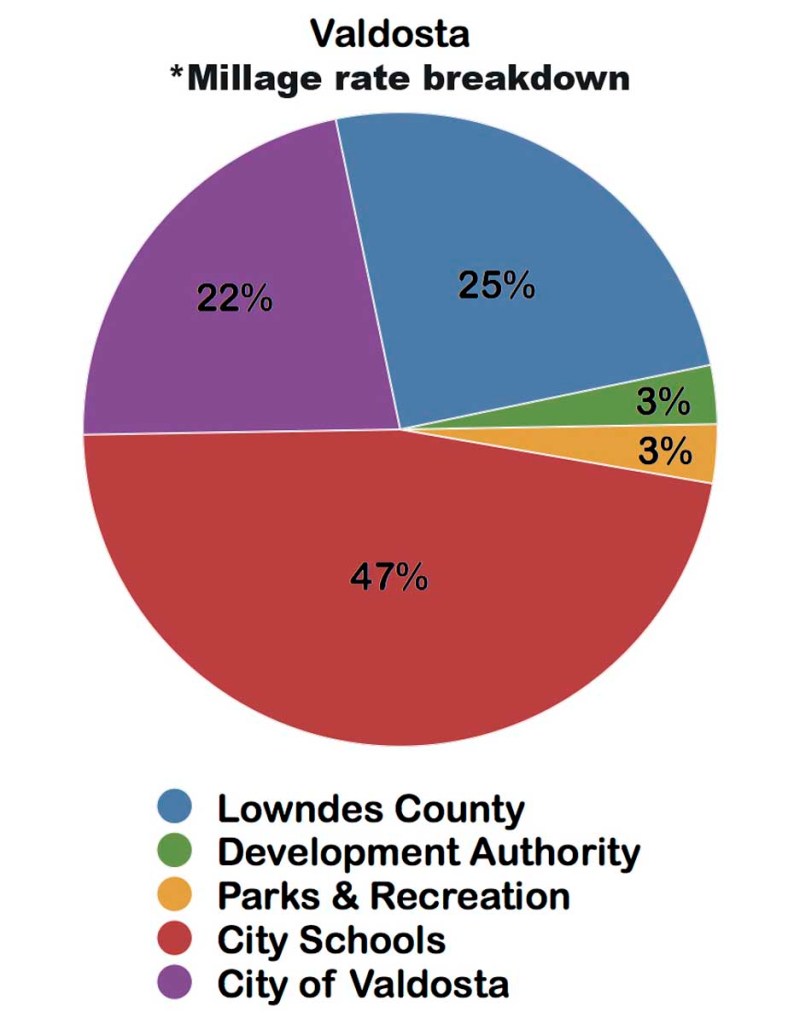

First of all, several millage rates factor into a final property tax bill. In addition to city and county rates, there’s a millage for city and county schools as well as special millages for agencies such as the local industrial authority.

Because cities are seen as an added layer of service, people living in cities have to pay a city millage on top of a county millage, as well as any other extra millages.

One mill equals $1 owed for every $1,000 of a property’s assessed value. Assessed value is how much a tax assessor says a property is worth.

So in simple terms, if someone owned property valued at $1,000 in a county with a millage rate of 5 mills, his or her property tax bill would be $5.

But a home/property owner doesn’t pay taxes on the entire assessed value, at least not in most places. Most governments in Georgia only tax 40 percent of a home or property’s assessed value.

Then, there are certain exemptions, such as for primary residences, that cut down the taxable amount even more.

When it comes to city and county millage rates in the SunLight area, most of the numbers fall in the 8-9 mills range: Baldwin County (9.8 mills), Tifton (9.7), Whitfield County (9.5), Thomas County (9.2 incorporated, 8 unincorporated), Milledgeville (9.1), Suwannee County (9), Live Oak (8.9) and Lowndes County (8.9).

To get an idea of what that means in dollar signs, a Baldwin County (unincorporated) resident with a $100,000 home would pay $394 a year (without exemptions) in property taxes. A Lowndes County resident in the same situation would pay $358 a year.

But remember that’s only how much is owed to the county. The other millage rates, such as the one for schools, bump up the total bill.

On the high end is Tifton at 12.1 mills and Moultrie at 12.8. At the tippy top is Colquitt County with 14.3 mills for unincorporated residents and 16.8 for incorporated. The incorporated rate equates to a $673 tax bill for a $100,000 home if exemptions weren’t on the table.

Valdosta falls just below the pack at 7.95 mills. A $100,000 home there would incur a $318 bill from the city annually. However, the widely used homestead exemption (for homes that are someone’s primary residence) would bring that number down to $270.

Way down the scale is Dalton with a rate of 2.5 mills. That seems like a steal, but Dalton doesn’t tax 40 percent of a home’s assessed value like the other governments. It taxes 100 percent of it, which is why the millage rate is much lower.

Even with the higher tax percentage, Dalton still collects well below the others. To put it in perspective, a person with a $100,000 home in Dalton would pay the city $250 in annual property taxes (excluding exemptions).

Dalton may be comparatively cheap, but the hands-down winner of bargain property taxes is Thomasville — the city government doesn’t levy property taxes at all.

In 2009, the Thomasville City Council made it a goal to eliminate property taxes altogether by 2012. It succeeded.

The city pulled off the feat by replacing property tax revenue with profits from Thomasville’s city-owned utilities. The utility companies — electric, water, wastewater, natural gas, solid waste and telecommunications services – are so successful that there are enough profits to fund police and fire protection, street maintenance and other essential governmental services.

“As City of Thomasville utilities are generally at or below the average for the state of Georgia, citizens enjoy the benefits of very competitive utility rates in addition to not paying additional property or fire taxes,” said Steve Sykes, city manager/utilities superintendent.

As evidenced by Thomasville’s non-existent property tax, each community has unique economic conditions, both good and bad, that determine how high property taxes are.

Which towns are facing property tax increases or decreases, and why?

As government revenues fluctuate from year to year, officials are constantly re-evaluating property taxes and deciding if the millage rate should go up, stay the same or go down. The other option is to slash the budget, which means no tax increase but fewer services.

Thomas County Manager Mike Stephenson put it like this: “(Governments) determine the level of services to the public and that determines the amount of revenue necessary to provide those services.”

So essentially, a change in any government’s millage rate hinges on whether the money is there or not, according to officials.

Whitfield County raised the property tax rate by 2.5 mills to 9.561 mills last year. The increase was projected to rake in about $6.25 million. In this case, it was about making up a financial deficit.

Whitfield County faced a $2.9 million deficit in 2016 without a tax increase and a projected $7.1 million deficit this year without the increase. Whitfield officials have long said they run a lean fiscal ship, but some county residents don’t see it that way.

“It seems to me that their first response to any problems is to raise taxes, not cut spending,” Whitfield resident Mary Jones said. “When the private citizen doesn’t have enough money, they have no choice but to cut spending.”

Dalton has cut its millage rate nine years in a row, but it may not be able to continue the streak this year. If revenues are down, the city could see a small increase, from 2.5 to 2.6 mills.

Mayor Dennis Mock said the city might avoid a tax increase but added the city may not be able to continue to cut taxes and provide the services he thinks residents want.

“We’ve really put off some capital spending,” he said. “When I go to the public works department and see the vehicles they are driving and the equipment they are using, I know we can’t keep doing that.”

Dalton resident Sam Woods questioned if perhaps the city’s services were a little too good and therefore too expensive.

“We have great services. I have no doubt about that, maybe the best,” he said. “But do we need the best? We could afford the best back when the carpet industry was booming.

“Can we afford it now? Can we continue to afford it? Maybe instead of the best we can settle for the really good.”

Live Oak’s City Council voted to increase its millage rate last year from 6.9 to 8.9 mills, and the raise was a long time coming. The state told the city that it needed to raise funds or it would risk running out of money.

Baldwin County’s last millage rate increase came in 2014 (8.84 to 9.84 mills), and the County Commission just met to explore the possibility of another increase in the coming year.

County Finance Director Dawn Hudson said leaders are waiting to get the latest tax digest info.

A tax digest is an official list of all taxable property and the amount of taxes that is owed in a given year.

If the digest amounts to less than expected, governments sometimes raise the millage rate to make up for the lost money. Until the digest is updated, the county won’t know for sure if property taxes will go up.

“It’s hard to say right now because we’re waiting on the digest information and there’s a calculation procedure we have to go through that will tell us what our rate needs to be set at to collect the current amount of revenue we’re collecting now,” Hudson said.

“Currently there are a few things that have been approved that will cause increases in next year’s (expenditures), but other than that we’re going to request our departments to keep their budgets level.”

Colquitt County last raised its tax rate in 2014, but the overall trend for a decade has been to cut property taxes.

“The millage rate is lower now than it was in 2007, which I think is pretty good,” County Administrator Chas Cannon said.

What Colquitt County does with its millage rate moving forward will depend on the growth in overall property value across the county. If it’s up, it could mean commissioners will cut the millage rate.

Suwannee County Commission Chairman Ricky Gamble said he’d like to cut the county’s rate from 9 mills down to 8, but he doesn’t want to reduce county services.

For the county to bring down the millage rate but keep services, Gamble said the county needs to work on improving property values and adding new homes and businesses to the county. With a larger tax base, he said, the county can spread out the tax burden, making it easier on everybody.

Lowndes County Commission Chairman Bill Slaughter is not ruling out a millage rate increase in the near future, but he too is eyeing potential growth as a way to fuel the economy and keep taxes down.

“If we had some growth, then that would more than likely prevent the millage rate from having to go up or having to go up as much,” he said. “But as long as our growth is very minimal, then the current millage rate that we use … is sustainable, but it doesn’t allow a whole lot of room for growth in the services that are provided for Lowndes County.

“I would think with any community that growth is an issue and is something that you look for. You want to grow. You don’t want to get stagnated as a community.”

Several local governments in the region have no plans to increase the millage rate in the coming year, including Valdosta, Thomas County, Tifton and Tift County.

The last Thomas County property tax hike was in 2013 when it set in motion a 40 percent increase.

Tifton made a big jump in 2013, going from 6.7 mills to 9.7.

During the last 25 years, Valdosta has lowered its millage rate 11 times and raised it twice. But the two increases came in recent years, 2014 and 2016. The 2016 increase hefted the millage from 6.1 to 7.95.

The city said the increase was needed to cover a decline in the tax digest, but the price bump also covered pay raises for city employees. Many in the community were outraged by the tax increase and said the city should have spread it out instead of dropping it all at once.

Tift County’s last millage rate increase was way back in 2004. While no increase is in the works this year, Finance Director Leigh Jordan said it’s hard to break even on certain services, such as courts and emergency-medical services

“We’re constitutionally created and we do these things and they’re generally not revenue generators. Look at ambulances. We bill for that but we’re only collecting about 52 percent of what it costs to run them,” she said. “We don’t have the ability to generate revenues like cities do.”

Moultrie City Councilwoman Lisa Clark Hill said she’s aware of the impact property tax increases have on residents, especially those with a fixed income.

The city’s last millage rate bump was in 2014 (10.9 mills to 12.8).

At that time, Hill said, only one person showed up during the three public hearings the state requires local governments to hold prior to increasing their millage rates.

“We think long and hard before we do something like that,” she said. “A lot of people don’t have that extra money, so I’m thinking about that.

“These decisions, as it relates to taxes, are made on the quality of services we want to provide for residents. (But) we listen to the people; they’re at the top. People think it’s the government at the top but it’s really about them.”

Moultrie, like Thomasville and unlike Colquitt County, has profit-producing services including utility, internet and cable television services, and some of those revenues can be used in its general fund, partially alleviating the need for a tax increase.

Often taxes go up even without a millage rate increase, and that’s where the rollbacks come in.

Sometimes millage rate decreases are required by state law

Often a piece of property remains unchanged but the assessed value still goes up, which would mean higher taxes. Georgia’s “Taxpayer Bill of Rights” is intended to prevent that indirect property tax hike.

Counties, cities, boards of education and any other taxing authorities are required to rollback millage rates if property values increase. The purpose of the rollback rate is so that individual property owners do not pay more in taxes simply because the value of their property increased due to inflation.

In the event of a reassessment, a rollback millage rate must be computed prior to ratifying the millage to ensure governments are collecting the same amount as before values increased. If a jurisdiction chooses not to rollback the millage, then it must advertise a proposed property tax increase and hold public hearings, making the public aware of the intention to raise taxes by not adopting the adjusted rate.

A failure to adopt the rollback rate in a reassessment year is a tax increase because increased property values will incur higher taxes even with the same millage rate.

So, even if a city, county or other jurisdiction leaves the actual millage rate the same as before a reassessment, it is not accurate to say taxes have not been raised.

Every community has its unique strengths and weaknesses, but in the end they all share a singular need: money to get things done.

Taxes: a ‘necessary evil’

Gamble — the one who has described government as a bloated money-eating machine — sides with the public in disliking taxes but believes they are a necessary evil.

Nobody wants to pay taxes, he said, but everyone is willing to pay their share of the burden as long as they are not being gouged and they can see something for what they are contributing.

“Nobody wants to feel like they are being taken advantage of,” Gamble said. “But most Americans don’t have a problem paying taxes.”

Live Oak City Councilman Frank Davis said taxes should always be sparse but still able to support community services.

“I’m under the belief that you should keep taxes as low as possible,” Davis said. “At the same time you have to be realistic. The government provides services. There has to be revenue, and taxation is one means.”

Valdosta Mayor John Gayle echoed that sentiment.

“It is important to understand that total property taxes alone would not even fund the police department budget,” he said, adding that property taxes make up only 12 percent of the city’s total budget.

“Local governments must have various revenue sources to fund the services citizens expect and to keep property taxes in line.”

Lowndes County’s Slaughter said as a businessman he understands that revenues and expenditures have to match.

“Those numbers have to correlate or you’re out of business. It’s just that simple,” he said.

“I don’t think anybody likes paying taxes … but there’s folks out there that understand that to be able to have the things that we need in this community, taxes are required. They just look for local governments to make sure that those services are provided responsibly.”

Residents are indeed looking to see that property tax increases produce results. When Valdosta raised its millage rate by 27 percent in 2016, one man commented on a Valdosta Daily Times article about the hike, saying, “I expect Valdosta to be a 27 percent better city then.”

His call for tangible results and government accountability is one heard repeatedly when taxpayer money is at stake.

The SunLight Project team of journalists who contributed to this report includes Patti Dozier, Thomas Lynn, Charles Oliver, Will Woolever, Alan Mauldin and Eve Guevara, along with the writer, team leader John Stephen.

To contact the team, email sunlightproject@gaflnews.com.