The Predator Next Door? Laws leave gaping loopholes for sex offenders

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 2, 2017

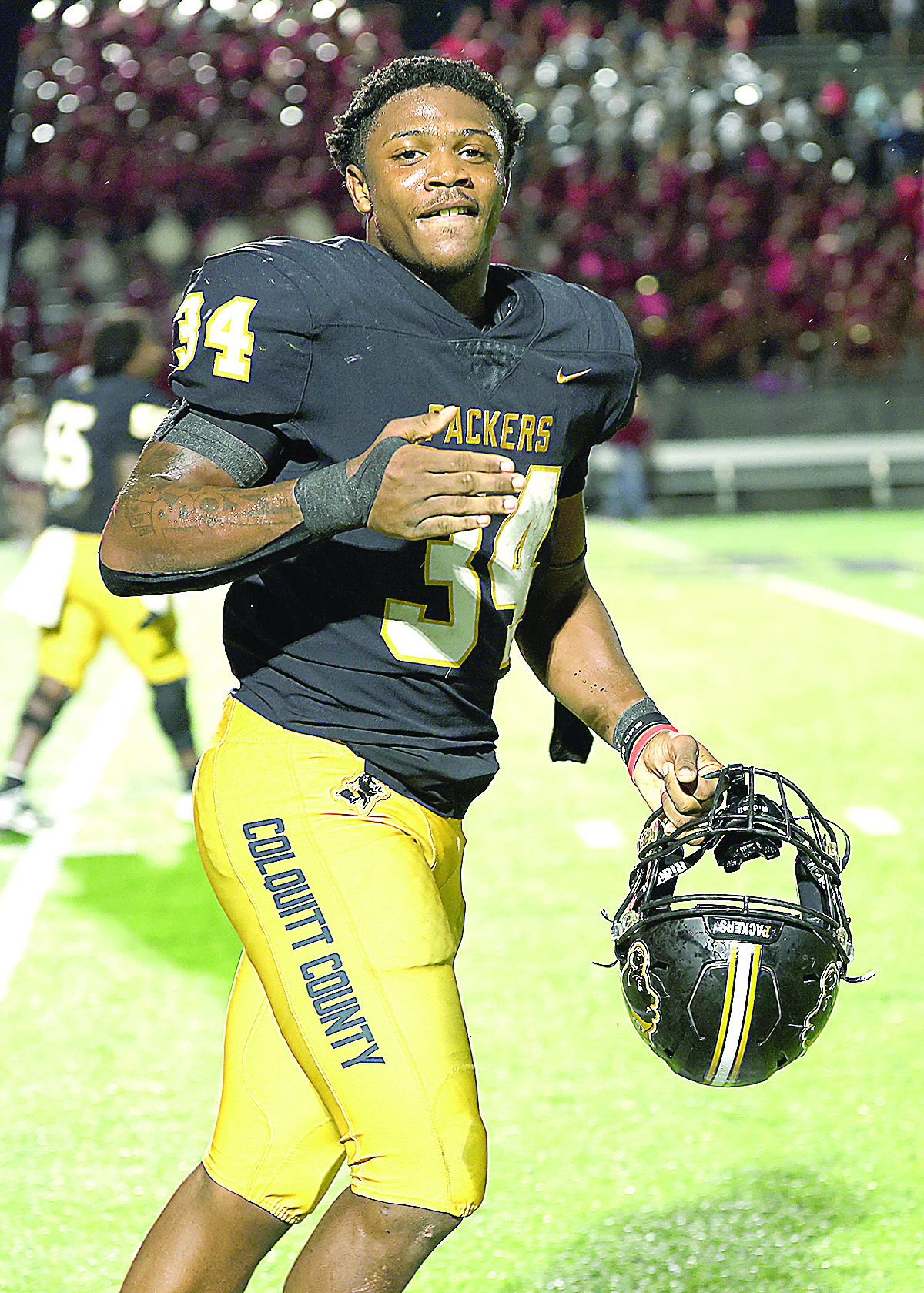

- Geudis Rivera

VALDOSTA — When Melvin Palmer set foot in South Georgia a few years ago, he had just spent 30 years in a Detroit prison for being a serial rapist convicted 10 times over.

Because Palmer committed his crimes before June 4, 2003, under Georgia law, he is allowed to settle down anywhere with no restrictions.

Yes, that’s right. Anywhere.

He can settle in a home next door to a school or day care or playground — anywhere.

“Melvin Palmer’s crime is so old (he) can live next to whatever he wants to. That’s not right. (But) that’s the law,” said Perry Connell, the Lowndes County Sheriff’s Office investigator who has monitored the county’s sex offenders, including Palmer, for the past six years or so.

Palmer currently lives at the Big 7 motel on West Hill Avenue in Valdosta, according to the local sex offender registry, but his freedom to live elsewhere highlights a glaring inequity in the way Georgia treats its offenders.

The state has a patchwork of varying restrictions for sex offenders, and what an offender can and can’t do is determined not by his or her offense but by the date of the offense.

For example, a convicted child molester who committed the crime in 2007 can’t go within 1,000 feet of a public swimming pool, but a molester with a 2005 offense date can hang around pools and libraries and even churches with the full support of the law.

Florida’s laws are much less fractured but still a far cry from uniform. Only certain offenses warrant restrictions, and even then, only when those offenses fall into certain time periods.

For the most part, Florida allows local cities and counties to create their list of sex offender do’s and don’ts, a process that has led to some of the strictest sex offender laws in the country.

The sex offenders — the molesters and rapists and assaulters — in the SunLight Project coverage area, which includes Valdosta, Dalton, Tifton, Thomasville, and Milledgeville, Ga., along with Live Oak, Jasper and Mayo, Fla., and the surrounding counties, are offered loopholes in the legal system because laws in the United States cannot be retroactive.

A Fragmented Justice System

Georgia law splits offenders into four time periods that become progressively more stringent, reflecting the state’s numerous pushes to tighten the rules.

If an offender committed a sex crime before June 4, 2003, he is under no restrictions at all unless a court specifically prescribes one.

Offenders whose crimes fall between June 4, 2003, and June 30, 2006, can’t live within 1,000 feet of child-care centers, schools or areas where minors congregate, such as parks, playgrounds and gymnasiums.

The next time period — July 1, 2006, to June 30, 2008 — adds churches and public swimming pools to the off-limits list.

The final period — July 1, 2008, and after — also bans offenders from public libraries.

In Florida, an offense date before Oct. 1, 2004, means the offender has no living restrictions unless imposed by local governments (an option many cities and counties take full advantage of).

Offenders who committed certain crimes — including sexual battery, child abuse and involvement with child pornography — against a child under age 16 on or after Oct. 1, 2004, can’t live within 1,000 feet of any school, day care center, park or playground.

But once again, many local laws in Florida fill in the gaps that state ordinances leave wide open.

Connell said Georgia’s mix of laws is frustrating.

“It’s not a perfected system yet. It is a constant, ongoing struggle,” he said. “I’m not going to say whether I think something is right or not, but it doesn’t seem fair to me.”

Connell said lawmakers, the “movers and shakers,” are aware of the legal inequities for sex offenders, flaws that are brought forth each year at a statewide conference for officers who monitor sex offenders.

Even though offenders have varying levels of freedom, they are all kept under close watch by vigilant law-enforcement officers.

The Watchmen

When offenders take their first breaths of freedom outside a jail or move from one address to another, they have 72 hours in Georgia and 48 hours in Florida to visit their local sheriff’s office and register as a sex offender.

An offender’s photo and crime are placed on the local online registry and printed in places around town for the public to peruse anytime.

From there, the offender has to come in periodically — once a year in Georgia and twice a year in Florida — to update his or her file with a fresh photo and any new information.

Sexual predators, who are offenders with a high risk of re-offending, have to visit twice a year in Georgia and four times a year in Florida. They also have to wear an ankle monitor until the day they die.

But offenders don’t just come to law-enforcement offices. Officers also go to them, visiting their homes and calling their workplaces to make sure they’re where they say they are.

Verification is crucial to maintaining public safety, said Lt. Tim Watkins, the chief investigator for the Thomas County Sheriff’s Office.

“If they re-offend, we’re responsible,” he said. “That’s why we take monitoring so seriously.”

Whitfield County Sheriff’s Office Detective Danny Headrick checks on offenders even when they don’t have a house or apartment.

“If they are homeless, they have to give us directions to where they are sleeping,” he said.

A number of years ago, lawyers told offenders if they claimed to be homeless, they would not have to register, he said.

“The law was then updated that said if you claim to be homeless, you have to tell us where you are sleeping. We have to have specific directions,” he said. “If you say you are sleeping under a bridge, I have to know what bridge, what color is your sleeping bag.

“In addition, we require the homeless to check in with us every week.”

Headrick has the county divided into sectors and goes through the list by sector.

“If I have some that might give me some reason for concern, I’ll jump ahead and get to them.”

In Florida, David Crutchfield, a corporal with the Suwannee County Sheriff’s Office, has to visit offenders at home once a year. For predators, it’s once every three months.

“That’s just the minimum amount of times I have to check up on them,” Crutchfield said. “If I’m in the area, for whatever reason, I’ll go and check up on them.”

Their willingness to participate is the greatest challenge he faces when keeping track of the offenders, he said. If they do not want to return to prison, they do whatever he asks them.

“There are guidelines they have to follow and they follow them to the tee,” Crutchfield said. “Some of them go too far.”

He said some offenders call him when they are going to a different city for the day. In those situations, he has to remind them he isn’t their probation officer. He doesn’t care where they go for the day, just as long as they see him at the scheduled times.

“Then there are some offenders who do not want to participate, and it’s like pulling teeth to get them to come in,” he said.

None of Suwannee County’s 94 offenders have ever given him too much trouble, he said, because they know if they don’t come and see him, they will return to prison.

In neighboring Hamilton County, Sheriff Harrell Reid said holding offenders accountable can be a challenge, especially for those trying to fly under the radar or give false information.

In addition to taking on frequent address verifications , Reid’s office mails a booklet of all offenders to every police department, day care and school in the county.

Each time an offender is added, a letter, an updated list and a photo/information sheet is mailed to add to the booklet. When an offender moves from the area, another letter and updated list is mailed advising to remove that person from the booklet.

In Tift County, once a new sex offender is registered, the sheriff’s office emails a photo with the name, offense, descriptive information and address to The Tifton Gazette for publication.

There are monitors located in the lobby of the Sheriff’s Office, courthouse and administration building running a list with information on local sex offenders.

Tift residents can even enter their home address and an email address on the TCSO web site and be notified when a sex offender moves into their neighborhood.

The sheriff’s office carries out address verifications once a month, and homeless offenders are verified weekly, said Lt. Col. Robert Brannen, who supervises the offenders in Tift County.

“Once violations are known or reported, an investigation is opened, and in the event sufficient probable cause is developed, a warrant is taken and the sex offender violator is arrested,” Brannen said.

Due to mental illness, many offenders have to be reminded of the rules, he said.

“Some of them are impaired or handicapped and you have to make sure they understand their responsibilities,” he said. “Some think when they finish probation or parole, they’re through with registering.

“In actuality, they’re on the registry for life, unless they meet the criteria to file a petition with the court to be removed.”

Many offenders are on parole or probation, so counties work closely with state and federal agencies to monitor and track offenders.

Thomas County’s Watkins said he’d rather see offenders locked up because then the sheriff’s office does not have to monitor them and the offenders can’t commit new crimes.

Georgia sex offender registration and monitoring is state-mandated and unfunded.

“It’s just dumped on the local sheriffs,” Watkins said, noting that Fulton County monitors 2,000 offenders.

The sheriff’s office registers about five sex offenders weekly. A Criminal Investigation Division employee spends a minimum of two hours a day on clerical work associated with sex offender activity.

The sheriff’s office must pay $5 a day for predators’ monitors while they are in Thomas County. Local schools and law-enforcement agencies must be notified about an offender’s presence and if the person moves or changes jobs.

As in other counties, Thomas County offenders’ photos are published in the Thomasville Times-Enterprise with their addresses so the public will know where they are.

A lot of offenders attempt to live at a Thomas County mobile home park — on Thomasville’s outskirts — because of its location across the street from a day-care facility, but authorities make sure they don’t succeed in the endeavor, Watkins said.

In Lowndes County, Connell verifies offenders every three weeks.

“Every day, I get a printout of who’s due, who to go check, who’s up. I’ve put 178,000 miles on my truck since 2011 or ’12, and that’s right there in Valdosta.”

Connell may never make contact with the offender during verification. He may simply drive by a home to make sure the offender is still there. He said some of his offenders haven’t laid eyes on him in six months, even though he’s seen them frequently.

Connell might also stop to speak with neighbors and ask if they’ve seen anything suspicious, such as kids hanging around.

“I want to talk to the people that don’t like (the offender) because those are the ones that’ll tell on him,” he said. “I can’t do anything about the kids being around, but I can keep my radar turned on if something funky’s happening.”

Not only does law enforcement keep a careful eye on offenders, they also house a vast wealth of information on offenders in case they try to repeat their sex crimes.

Tiny Details and Big Differences

Often, catching a sex offender — and proving it in court — can come down to the smallest personal attribute — a hidden tattoo, a brand of beer, a bumper sticker.

That’s why when sex offenders register with law enforcement, they go through an exhaustive intake process that allows authorities to glean a vast array of information.

Family relatives are listed, along with their phone numbers. Preferred brands of cigarettes and alcohol are written down.

Connell described a scenario where an offender might be peeking in a window a 6-year-old, flipping a cigarette butt on the ground and leaving it behind, saying authorities would get the DNA and catch the offender.

Tattoos are photographed, no matter where they are.

“You’d be amazed where people get tattoos,” Connell said. “You get a 6-year-old little girl, she may not even know what a ‘thing’ is called, but if it’s got a tattoo of an anchor on the end of it, she knows it.”

If an offender has a vehicle, it’s also photographed, with close attention paid to distinctive features, such as dents and bumper stickers.

“If they’ve got one little sticker that shows a blue-striped surfboard, we’ll take a picture of that surfboard — anything that makes that car unique,” Connell said. “A little kid will say, ‘I don’t remember anything, but there was a mouth with a tongue sticking out’ — a Rolling Stones sticker. Kids pick up on stuff like that. Grown-ups pick up on stuff like that.”

Most offenders willingly offer the extensive information because they have no plans to re-offend, Connell said.

“Most of them come here with the forethought of, ‘I’m going to be perfect, and I’m getting this crap behind me.’ (But that) doesn’t always happen,” Connell said.

Detective Haley Beckham is a five-year member of the Georgia Sex Offender Registry Task Force, a body of the Georgia Sheriff’s Association that monitors offenders’ whereabouts across 10 regions statewide. She oversees 15 counties from as far south as Houston to as far north as Morgan.

She said being able to search offenders by distinctive characteristics — such as vehicles, scars, marks, tattoos, addresses and phone numbers — is a great way to keep people informed about which offenders are in the area and where.

“If you have somebody in the community that’s being harassed by a number, or if they think that their child is being targeted by an offender, I can search that number they have listed if it’s in our database,” Beckham said.

“I can’t tell you how many phone calls I get where someone will ask me if I’ll tell them what sex offenders live in their community. I’ve honestly had one case where I had to say, ‘Which one?’ because there were three living in her community.”

Although the public is often eager to know when an offender is in the neighborhood, many offenders go to great lengths to not be recognized around town.

The Disguise Game

Most offenders have to visit local law enforcement once or twice a year to update their picture and their file — do they have a new car, a new tattoo, etc.

But many will try to change their appearance around picture time so that what they look like in the registry is strikingly different from what they look like on the street, Connell said.

One of his offenders, Billy Smith, was the “world’s worst” at this, Connell said.

“He would come in here completely clean-shaven, have a good haircut, and he would take his glasses off before he’d come in,” Connell said.

“When you took his picture, Billy Smith didn’t look like Billy Smith. But by the time he left here, in two weeks, he’d have a goatee, his hair had grown out, and he’d have his glasses back on and a ball cap on his head. So we’ve got pictures of Billy Smith several different ways.”

Beckham said many will try to change their name to escape their past.

“But that’s something that we can arrest them for,” she said. “I typically have about one per year that will violate the registry.”

Connell said in Lowndes County, he doesn’t see a lot of offenders committing more sex crimes, but he does see a whole lot of smaller violations, such as failing to register yearly or withholding pertinent information.

And when an offender doesn’t play by the rules, it’s not just a slap on the wrist.

“Every charge I take is a felony; there is no misdemeanor here,” Connell said.

Beyond the offenders who disguise themselves and the ones who occasionally step out of bounds, there are the ones who try to buck the system altogether. They are the runaways, the absconders — the ones who vanish and go rogue.

“They’re MIA, off the grid and they’ve got a warrant (for their arrest),” Connell said.

He said one of his absconders is probably hiding out with his family’s help.

“But he’ll slip up,” Connell said. “They are creatures of habit. They cannot stay out of sight.

“I’ve got one that’s probably in Cuba. Not kidding at all. He was registered for two days, then I never saw him again.”

Beckham said absconders could drift into any community.

“There are thousands of absconders just from Georgia alone, so if you look at the statistics, odds are there could be someone who’s on the run in your community,” she said.

Although sex offender registries are marked by many depraved and malicious characters, not all offenders are created equal, and some are far less dangerous than others, authorities said.

‘Not All Monsters’

Thumbing through the registry of his offenders as though flipping through a twisted, sinister yearbook, Connell commented on the pictures of the men he knows through and through.

This one molested both his daughters, he said. This one works on the family farm and is never a problem. That one has a mental disorder and is totally out of it. This one used to be a high school coach. That one is bag boy at the grocery store. This one is a heartbeat away from a highlight reel, he said.

Connell’s relationship with his offenders is unique and strange. He knows the intimate details of their lives. He has a closeness to them that is usually found only in friendships, but he is not their friend.

They are still sex criminals and being immersed in their lives day in and day out takes its toll on him, Connell said.

But because he knows all about them, he knows not all of them are monsters.

“We throw them all in the same melting pot and that’s not right,” Connell said.

One offender who has since moved away was convicted for having consensual sex with his underage girlfriend, Connell said.

“(She) was his long-time girlfriend, who is now the mother of his children and the grandmother to his grandchildren, but yet he’s on the sex offender registry. He is just simply titled sex offender,” Connell said.

Although not an overwhelming group, many offenders end up on the registry with the child molesters and rapists for sleeping with their girlfriend, Connell said.

One of those men is a 34-year-old who lives in Hahira.

“When he was 21, 22, she was like 15. He has been no problem ever whatsoever. He’s home all the time, has a family (and is) a functioning, working part of society. And he has to deal with me every three weeks,” Connell said.

“Not all of these men and women on this registry are monsters. You’ve got some hardworking people in here that screwed up. You know, they were a few years older than their girlfriend. (They are) hardworking family men.

“(But) a lot of them aren’t.”

And because many of them actually are monsters, Connell said, it’s crucial the public knows their faces and can recognize them.

“This is everywhere,” Connell said, thumping the registry printout sitting in front of him. “This is at the courthouse and the post office and online. We’re keeping the public informed, and the public is becoming more and more aware of this list.

“Be aware. It’s common sense. Check your sex offender registry. See if it is somebody that you’re dealing with. These guys have jobs all over Lowndes County.

“You just don’t ever know where you’re going to encounter one, so you need to be aware of your surroundings.”

The SunLight Project team of journalists who contributed to this report includes Eve Guevara, Patti Dozier, Will Woolever and Charles Oliver, along with the writer, team leader John Stephen.

To contact the team, email sunlightproject@gaflnews.com.

Popular Homes for Lowndes County Offenders

Big 7 Motel (West Hill Avenue)

Travelers Inn (Madison Highway)

Lowndes County Sexual Predators

(Offenders with a high risk of re-offending)

Dewey Booth

3131 N. Oak St. Ext.

Apt. 11A

Valdosta

Brian Scott Cudney

720 E. Park Ave.

Apt. 3

Valdosta

Michael Anthony Turner

4027 Woodtrail Drive

Valdosta

Willie James Williams

605 E. Gordon St.

Valdosta

Lowndes County Absconders

(Offenders who have gone rogue, whose whereabouts are unknown)

Raynard T. Bevil

Michael Daniels Jr.

Jarrell Tevester Prince

Geudis Rivera

Breakdown of Crimes for Lowndes County’s 257 sex offenders:

Child Molestation: 67 (26%)

Statutory Rape: 46 (18%)

Sexual Battery/Assault/Abuse/Conduct: 42 (16%)

Rape: 26 (10%)

Sexual Exploitation/Enticement of Children: 23 (9%)

Lewd and Lascivious Acts: 14 (5%)

Incest: 7 (3%)

Obscene Internet Contact: 7 (3%)

Sodomy: 7 (3%)

Other: 18 (7%)

To view the Lowndes County Sex Offender Registry, visit www.lowndessheriff.com.