To Serve & Protect

Published 3:00 am Sunday, February 19, 2017

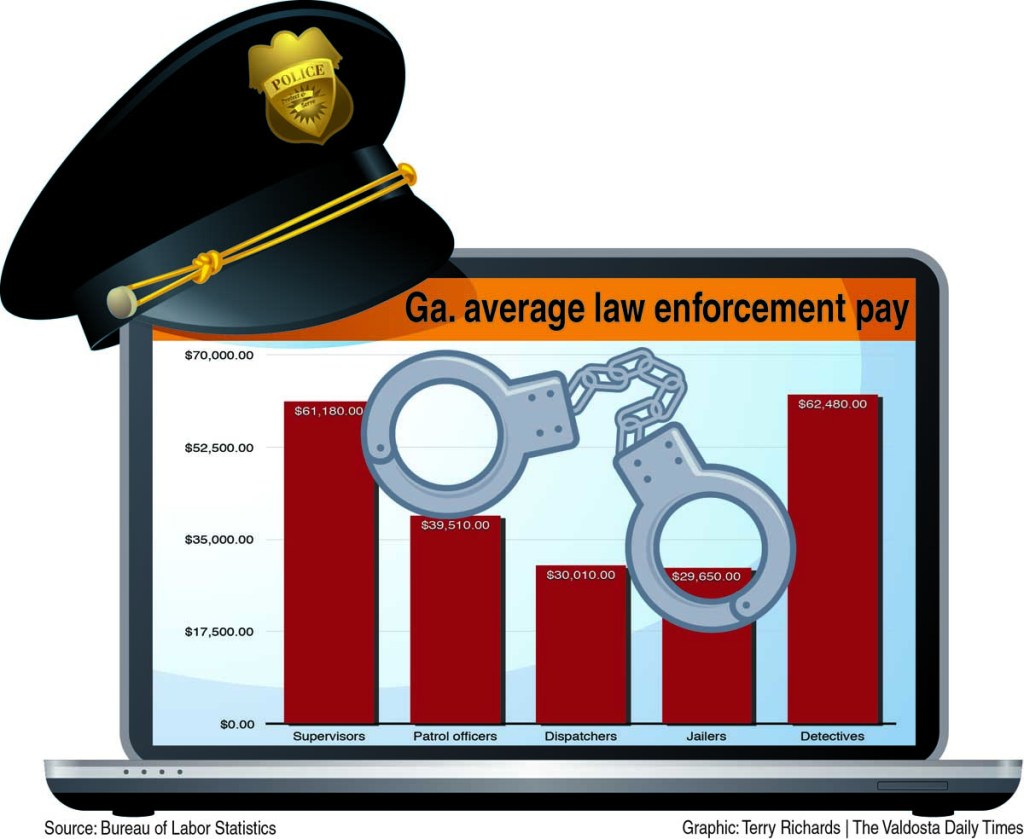

- Statewide police pay

VALDOSTA — There was a time — back before 10-year-olds had smartphones and iPads — when children would put on a sheriff’s star and strap on a six-shooter cap pistol to be the “cop” in a game of Cops and Robbers.

Starry-eyed boys and girls dreamed of becoming police officers. Or astronauts. Or professional football players.

Trending

While many young people may still aspire to fly to Mars or be the Super Bowl MVP, law-enforcement agencies in the SunLight Project coverage area are struggling to find people to join the force — and to stay put once they do.

A formidable mix of negative perceptions and low salaries is driving the declining interest in law-enforcement jobs. And it’s a problem police departments and sheriff’s offices across the South are facing.

Multiple police shootings in recent years have sparked nationwide protests and heated discussions regarding police brutality, and the law-enforcement brand has suffered as a result, police chiefs and sheriffs said.

The national climate has created an “open season” on law enforcement, one police chief said, making an already dangerous job even more perilous — and making the recruiting process even more difficult.

The other huge problem is low pay. Current salaries don’t compensate for the danger officers and deputies face daily and are not strong enough incentives to keep employees in one place for long, multiple chiefs and sheriffs said.

In the SunLight Project coverage area — Moultrie, Dalton, Tifton, Milledgeville, Thomasville and Valdosta, Ga., along with Live Oak, Jasper and Mayo, Fla., and the surrounding counties — starting salaries for law enforcement range from $25,000 to $37,000.

Trending

Even though many city and county governments in the region — the people who control the purse strings — have worked in recent years to increase law-enforcement pay and have done studies to ensure pay is competitive in the marketplace, it’s still not enough, chiefs and sheriffs said.

Local economies are still recovering from deep recession and there are only so many dollars available in a city or county budget. Furthermore, government officials have to consider the needs of all of the departments within their jurisdiction, not just law enforcement.

Regardless, low law-enforcement salaries have significantly impacted recruitment and retention in the region as prospective employees opt for better-paying professions. On top of that, Current employees are searching out higher wages at other agencies.

The Competition Problem

Last year, Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal gave state law-enforcement personnel a hefty 20 percent pay raise, pushing salaries for state officers from dead last in the nation to 24th.

The increase, that went into effect Jan. 1, added about $8,000 to a state officer’s yearly income.

The median starting salary for state law-enforcement officers is now about $46,500.

In Florida, entry-level pay for state cops is about $34K, but can be significantly higher based on where troopers are assigned.

Deal and Georgia lawmakers said the raise was badly needed and long overdue. But it created an unintended consequence.

Local agencies in Georgia that can’t afford to match the new state pay are now at a deeper disadvantage when competing to retain employees.

Not long after Deal announced the state pay increase, one of the Dalton Police Department’s most senior officers left to take a job with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

“That person had almost 20 years experience, had a master’s degree, had a high level of training (and) had served in many different positions for us,” Dalton Police Chief Jason Parker said.

“You can hire someone to fill that slot. But you can’t replace that experience,” he said.

A police officer in Dalton, a town of about 34,000, has a starting salary of $31,500.

Whitfield County Sheriff Scott Chitwood said he lost an experienced deputy to the GBI a year and a half ago, well before Deal announced the pay increase. But he said the higher pay makes it more likely his agency and others will lose officers to the state.

And that trend will persist if local governments aren’t able to increase salaries, he added.

“It isn’t just retention that’s going to be a problem,” Chitwood said. “We think that a lot of the candidates that were once giving us a first look are now looking at those state jobs.

“Our applications have dropped since last summer. We can’t say for sure, but we think that people are now looking at those state jobs first, since there’s the potential for a fairly high pay.”

Whitfield County, which has about 104,000 residents, pays deputy sheriffs a starting salary of $29,900.

“Would you rather start at an agency that starts at $29,000 or one that starts at $40,000?” Chitwood said.

Tift County Sheriff Gene Scarbrough said he’s lost almost a dozen people in the last year and a half.

“All of them went to a different agency,” Scarbrough said, adding that two of his people went to state agencies since the state raise was announced.

Tift County, with a population of about 41,000, pays deputy sheriffs a starting salary of $29,000.

“Our plight of hiring and retaining personnel was exponentially exacerbated last September when Gov. Deal announced that all state law-enforcement personnel would be receiving a 20 percent increase in pay,” Scarbrough said.

“Let me be very clear here, I absolutely support those officers getting a raise and think they deserve it. On the other hand, though, if the state officers deserve a 20 percent increase, local city and county officers deserve the same if not more.”

Scarbrough said benefits are a big issue for his people. They want the same insurance that state agencies offer, which would mean paying less for better coverage.

Dalton’s Chief Parker said even before Deal announced a large pay increase for state law enforcement, competition from other agencies and the private sector was becoming a concern.

“There was a time, say 10 years ago, our agency had a high rate of compensation relative to others. That was enough to keep people from looking for greener pastures. Now, we are experiencing some difficulties,” Parker said.

During the Great Recession, budget cuts affected departments across the state, but other local governments have been quicker to boost spending as the recession ended, Parker said.

“In 2009 and 2010, we had virtually nobody leave because the jobs weren’t out there. But as the economy has picked up, we are losing people not only to other local agencies and to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and the Georgia State Patrol but to the private sector,” he said.

Some local agencies say they haven’t been negatively affected by the state’s pay raise, at least not yet.

One such agency is the Tifton Police Department, but Chief Buddy Dowdy still thinks the increase could eventually hurt his department.

“I don’t know what kind of impact it’s going to have, but there’s certainly no good going to come out of it for local law enforcement,” Dowdy said.

Police officers in Tifton, a town of about 17,000, receive a starting salary of $30,700.

Regarding pay increases for state law-enforcement officers, Thomasville Police Chief Troy Rich said, “I have not felt the impact yet in my department.” If a TPD officer opted to join the Georgia State Patrol, “I’m not opposed to it,” he added.

Thomas County Sheriff Carlton Powell said the 20 percent pay hike for Georgia State Patrol troopers might affect his force.

“There’s been no impact yet. It’s new,” Powell said.

Benefits also are important, he said, but local governments struggle to keep officer pay competitive.

“Some of them get tempted by the quick money you can make at a bigger department, a state position or even at the federal level,” Powell said.

State Rep. Dexter Sharper, D-Valdosta, said the state isn’t intentionally trying to poach law enforcement from local agencies.

The state was just taking care of its officers and trying to help with recruitment, he said. It’s natural, he added, that some of those recruits will come from local departments.

Still, he doubts local officers are going to leave departments en masse. Officers with deep roots may prefer to stay put.

But if the departures become significant, Sharper said he doesn’t see a role for the state in addressing the issue.

“I have faith in our city and county leaders that they’ll do what they need to do, that if they feel the risk of a lot of people leaving that they’ll go up on their salaries for their people,” he said.

In light of the state raise, the Georgia Sheriffs’ Association called for lawmakers to pass legislation that would bring pay for local officers up to the same level as state officers.

Additionally, the Georgia Association of Chiefs of Police issued a resolution asking local governments to review law-enforcement salaries to ensure they are competitive with the rest of the state.

“The struggle to recruit and retain high-quality law-enforcement personnel continues to be a central law-enforcement concern statewide. The issue of substandard salaries and associated benefits are a significant hindrance to effective recruitment and retention,” the resolution said.

While many agencies applaud the statewide efforts for better pay, Valdosta Police Chief Brian Childress said there are potential problems with assigning a blanket salary across the state.

Childress has inspected more than 50 law-enforcement agencies in the U.S., and he emphatically agrees officers in the South are substantially underpaid compared to the rest of the country.

However, he thinks asking the state to pay local salaries is unrealistic.

“It is the burden of local governments to ensure salaries of law enforcement are where they should be,” Childress said. “Second, I do not agree with a flat minimum salary for all of law enforcement. I think certain law-enforcement agencies should be paid more than others based on workload and professionalism.

“One thing Valdosta City Manager Larry Hanson considered when looking at our salaries a few years ago during the pay and compensation study was our call volume and the fact we have three voluntary accreditations.

“As a result, salaries were compared to agencies of like size, population, and if they were accredited or not. Like any other job, more work demands higher salary. For example, in many cases, crime and call volume is usually much higher in cities because, like in Valdosta, roughly 50 percent of the county population resides in 38 square miles of Valdosta city limits. Therefore, city officers answer three times more calls than deputies in unincorporated areas. As a result, I stand strong that my officers should be the highest paid in the county and South Georgia region.”

Valdosta, a city of about 56,000, pays its officers a starting salary of $37,000, an amount reached after the city granted a pay increase last year.

Childress said his employees’ salaries are where they should be so long as there is a cost-of-living and merit raise factored into each budget year.

“Georgia, like every other state in the U.S., is recovering from a lengthy recession where starting salary increases and raises just were not given out because of lack of funding.”

Childress said he believes the real culprit can be traced back to the way sales tax is collected.

“If you buy something locally in Valdosta or any other city, there is a local sales tax that comes back to local governments to help them adequately operate their counties and cities,” Childress said.

“Because of dramatic increases in online purchases in Georgia and the fact there is no ‘teeth’ to enforce the collection of sales tax for those online sales, places like Valdosta/Lowndes County and other Georgia governments are suffering. Some states have addressed this but Georgia is certainly one that has not.

“The results: no money to pay for cost-of-living and merit increases.”

The Budget Problem

Chiefs and sheriffs regularly lobby their local governments for employee pay raises, and many have succeeded.

Baldwin County Sheriff Bill Massee said he knew the state pay raise could cause the loss of quality deputies, a problem his office has encountered many times through the years.

The only thing he could do was to seek pay increases from the county commission.

“I thought it was only fair to ask our county commission for pay raises for our people in light of what the governor had proposed at the time,” said Massee, a six-term sheriff, and former president of the Georgia Sheriff’s Association.

Subsequently, commissioners found the extra funding in the county budget and deputies and detectives were given pay increases.

A starting deputy with the Baldwin County Sheriff’s Office is now paid $35,800. A starting detective in the county, which has about 45,500 residents, earns $37,600.

Tifton’s Chief Dowdy said a 2016 pay raise for his department went a long way in helping retain employees.

“The city stepped up to the plate,” Dowdy said. “It went up from $13.95 to $16 (per hour), and then they also got a 3 percent raise in July. But [the city] understood how many officers we were losing. We lost nine officers in two months.”

Pay was a contributing factor in officers moving elsewhere, Dowdy said.

The City of Thomasville always budgets 3 percent annual, performance-based merit raises for all employees. Thomasville, a town of about 19,000, pays police officers a starting salary of $30,000.

Chief Rich said in his 27 years with TPD, he has not missed a merit raise and knows of no other employee who has.

“The City of Thomasville believes in retaining quality employees,” the chief said.

Thomasville government conducts a salary study every four to five years and compares city salaries to others in the region to determine if pay is meeting or exceeding the market.

A TPD officer who is promoted receives a 5 to 10 percent pay hike.

“Pay is a small part of morale. Police officers don’t make a lot of money,” Rich said.

The Thomas County Sheriff’s Office got a raise as part of a boost for all county government employees — two cents an hour for the number of years employed by the county.

In addition, patrol deputies received raises of $1 an hour.

Thomas County, with a population of about 45,000, now pays deputies a starting salary of $27,700.

Local law enforcement heads must convince their respective governing bodies about officer pay increases, the sheriff said, adding he received “a pretty good reception” from Thomas County commissioners about his request for higher pay for patrol deputies who work at night.

With security a concern in many areas, the sheriff’ office receives requests for security personnel.

“Law enforcement can fulfill some of these and provide supplemental income for officers,” Powell said. “These are things that are advantageous to law enforcement and affects possible shortcomings in pay.”

Suwannee County, Fla., Sheriff Sam St. John is confident he can work in some pay increases for his employees in the next year.

The county is helpful and understanding where pay increases are concerned, St. John said.

“I feel confident I can get one but how much it’s going to be is really the question,” St. John said. “I put in what I think the employees deserve versus what the county can afford to give me. It’s a balancing act.”

Suwannee County, which has about 44,000 residents, pays deputy sheriffs a starting salary of $32,000.

Other agencies in the region don’t know when their next pay raise will come.

Live Oak, a town of about 7,000, hasn’t give its police department a pay raise in six or seven years, Police Chief Buddy Williams said.

“Pay raises and advances are few and far between,” he said.

Live Oak police officers start at $31,300.

Williams emphasized that investing in current staff is cheaper than having a high turnover rate.

Live Oak police are beginning their budgeting process now and just like every year, he said, they talk with the city about pay increases. Williams wasn’t confident a pay increase would be coming.

“We’ve learned that all you can do is cross your fingers and hope something comes,” Williams said. “Do not get me wrong, our pay is average for our size and area.”

As a former county commissioner, Lowndes County Sheriff Ashley Paulk knows how difficult it can be for local governments to find the money needed for pay raises.

“Every department is always looking for additional personnel and different things they need. You’ve got to balance everything out as a commissioner to see how much money you have to do what with,” Paulk said.

Lowndes County, which has about 113,000 residents, pays its sheriff’s deputies a starting salary of $34,400 — a number Paulk said he’s always trying to increase.

The Experience Problem

When low pay forces officers to jump around in search of better wages, an agency’s overall experience level is diminished.

At the moment, the Colquitt County Sheriff’s Office is fully staffed with the exception of one school resource officer, but that doesn’t tell the whole story, Sheriff Rod Howell said.

Fifty-three percent of the staff have less than five years experience, indicating high turnover.

“When you’re putting a football or baseball team together, that’s not what you want,” Howell said. “I want to see that number go down.”

Sixty-five percent have less than 11 years in law enforcement.

Officers with 12 to 23 years currently make up only 3.2 percent of the staff.

“Less than 1 percent have 24 to 29 years,” Howell said. “That’s what you’re getting into with the (pay) is the turnover rate. We get them trained, and they leave us for the money they can make out of the county, and I don’t blame them for trying to do better for themselves and their families.”

Finding Incentives to Stay

When pushing for pay raises that may or may not materialize, local chiefs and sheriffs look for other incentives to help attract and keep quality employees.

Officers in Live Oak are given a take-home car package, uniform and laundry services, life and health insurance and a clean, workable facility at the police station.

To combat someone leaving, Live Oak’s Chief Williams encourages building a bond between everyone in the department. He said they are more of a family in a smaller department than in larger ones.

“I think we do very well at keeping people,” Williams said. “You don’t always have a happy house, but we do our best to keep morale high.”

To compensate lower rates, Suwannee County Sheriff St. John said he too focuses on creating a healthy work environment and building loyalty with his officers.

He also gives them incentive pay that rewards officers for taking law-enforcement classes. The pay isn’t much, a maximum of $1,500, but it can make a difference, he said.

Many agencies offer extra money for higher levels of education. But money isn’t all employees need, Lowndes County Sheriff Paulk said.

“You’ve got to let the people know you care about them. I try to run this like a family. Everybody down here is important to me,” Paulk said.

And in the end, the best incentive to stay may be something that a chief or sheriff can’t provide: passion for the job.

“Nobody is in law enforcement for what they make. It’s just something that gets in your blood, something (you) love to do,” Paulk said.

The SunLight Project team of journalists who contributed to this report includes Thomas Lynn, Charles Oliver, Eve Guevara, Billy Hobbs and Patti Dozier, along with the writers, Alan Mauldin and team leader John Stephen. Jill Nolin also contributed to the report.

To contact the team, email sunlightproject@gaflnews.com.