In the Hands of Criminals

Published 3:00 am Sunday, January 15, 2017

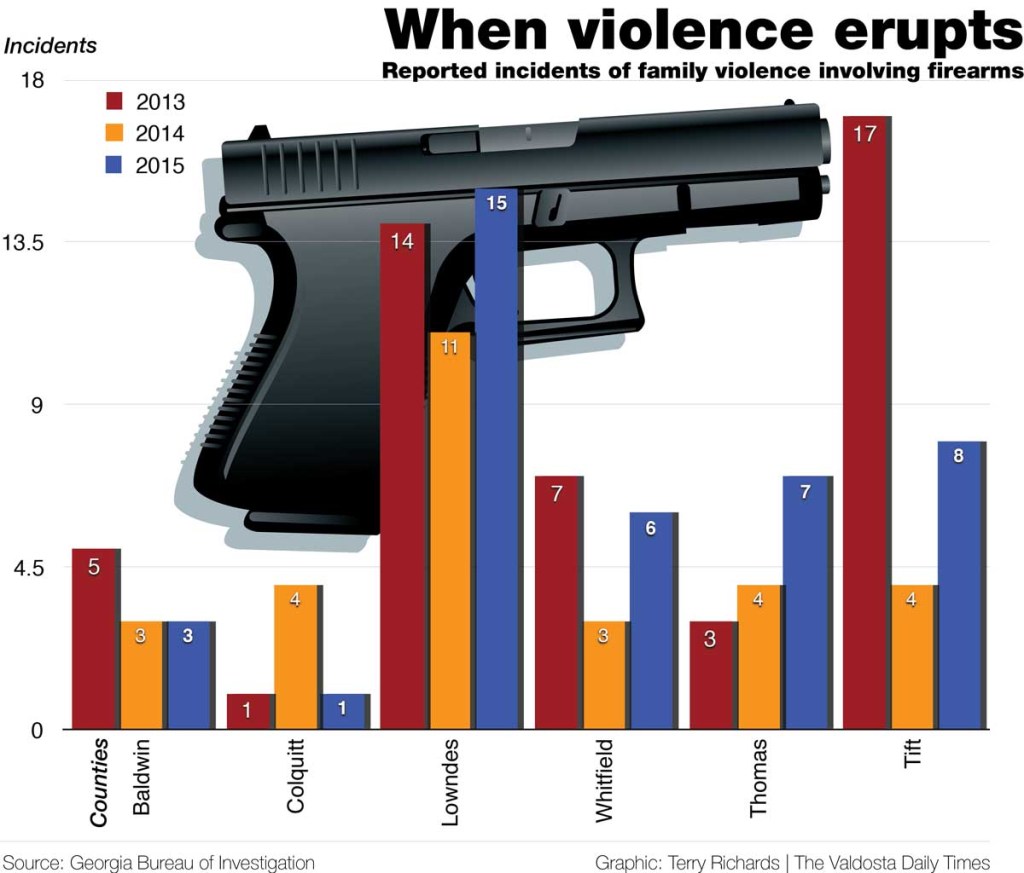

- Guns in Family Violence

VALDOSTA — John Hester Sr., 68, was shot in Colquitt County in July 2015 while trying to defend his son’s home from six teenage burglars. He later died from his injuries.

Just hours before the shooting, the six teenagers had stolen pistols, rifles and shotguns from the home of a Norman Park City Council member. One of those guns fired the bullet that ended Hester’s life.

Trending

A stolen gun used in a fatal shooting.

In the murky, underground world of illegal gun activity, gun thefts and gun crimes go hand-in-hand, said multiple law-enforcement officials from across Georgia and North Florida.

However, police chiefs and sheriffs in the region are split down the middle on how gun thefts relate to gun crimes.

Some chiefs and sheriffs argue gun thefts are not directly linked to gun crimes because guns are often used as currency rather than weapons. Stolen guns are traded for drugs or sold many times for cash, they said.

Regardless, law enforcement officials from the cities and counties throughout the SunLight Project coverage area — Valdosta, Tifton, Moultrie, Thomasville, Milledgeville and Dalton, Ga., along with Live Oak, Jasper and Mayo, Fla., and the surrounding counties — generally agree. Gun theft leads to weapons ending up in the hands of the wrong people.

Such thefts frequently come about as a “crime of opportunity,” police say, meaning people steal guns because it’s convenient. A criminal is robbing a home and happens upon the firearms, or a gun is left in an unlocked car, making the theft easy.

Trending

Unreported gun thefts make it hard to get accurate numbers on that specific crime, authorities said.

Even the ones they know about can be hard — if not impossible — to track if the gun’s serial number is unrecorded, which is often the case with guns bought from a private seller.

But as law-enforcement agencies investigate gun theft, one thing is clear: the conclusions they draw regarding such crimes are often pointedly different.

Is there a link between gun theft and gun crime?

Overall crime in Valdosta, a city of 55,000, has decreased during the past 15 years, but Police Chief Brian Childress said aggravated assaults involving guns have been on the uptick in recent years.

Valdosta police recorded 156 gun thefts, 45 aggravated assaults involving guns, and six gun-related homicides in 2016. Childress said gun thefts “absolutely” influence the other two crimes.

“What we see here, and I think what you’re going to find across the country, is gun crimes are normally committed by people who shouldn’t have had (them) in the first place. Not legal owners,” Childress said.

“Anytime you have guns stolen, the people that are stealing them are more than likely a convicted felon. There’s a high probability they have no business having them in the first place.”

Lowndes County Sheriff Ashley Paulk agrees, saying the “bad guys” are stealing the guns, probably because they can’t get a gun legally due to their record. The bad guys then turn around and use the guns to commit additional crimes.

Police chiefs and sheriffs from places such as Live Oak and Moultrie said they too see a direct relation between gun thefts and gun crimes in their jurisdictions.

Crunching The Numbers

While the number of gun thefts and gun crimes rise and fall from city to city, it’s hard to say if one city is struggling more with illegal gun activity than another, said David Sparks, a crime analyst for the Albany Police Department.

“No two cities or jurisdictions are the same and really should not be compared to one another,” Sparks said. “The only true comparison that can be made is a city or location compared to itself, year to year.”

In Suwannee County, Fla., which has a population of 44,000, the year-to-year data shows a clear tie between levels of gun theft and aggravated assaults.

The Suwannee County Sheriff’s Office recorded 37 aggravated assaults in 2014. An estimated $26,000 in firearms was stolen the same year.

Two years later in 2016, the number of aggravated assaults was cut in half to 18, and the total value of guns stolen followed the same pattern, dropping to $13,700.

However, law-enforcement agencies from across Georgia, including areas such as Tifton, Milledgeville and Dalton say they generally don’t see a problem with stolen guns being used to commit crimes.

In Lafayette County (near Live Oak), only two crime cases in 2016 involved a stolen gun.

Dalton Police Chief Jason Parker said while 39 guns were reported stolen in 2016, the city simply hasn’t seen many weapons-related crimes that involve the use of a stolen gun.

In Baldwin County, law enforcement investigated 81 gun thefts, 78 aggravated assaults involving guns and five gun-related murders. The total value of the stolen guns was $31,317.

Capt. Brad King of the Baldwin County Sheriff’s Office said stolen guns have impact on the street due more to their trade value than their ability to shoot people.

Lt. Lee Dunston of the Tifton Police Department agrees, arguing stolen guns are used less as crime tools and more as a “hot commodity,” a means to an end.

Guns, drugs and money

When guns are stolen, they will probably change hands many times before they are actually used in a crime, if used at all, some law-enforcement officials say.

Usually the guns are traded or sold to get two things: drugs and cash.

“On the streets firearms are a currency. Firearms are treated the same as money,” Baldwin County’s Capt. King said. “The theft is generally not done by the guy who does the shooting. The theft is done by the crackhead.”

Once in Tifton, several guns were stolen from a home and within two hours they had changed hands at least five times, going from the burglar’s hands to a semi-reputable or reputable person before being recovered, Dunston said.

“Drug dealers know they can get rid of them, because there is always someone in the market for a gun around here,” Dunston said.

He added guns are also attractive because they will fetch a better return than other goods such as a television or a cell phone.

Because stolen firearms change hands so quickly, the person using a stolen gun in a crime will most likely not be the same person who originally stole the gun, authorities have said.

“If you have a criminal break into someone’s house and steal a gun, there’s a (probability) that he’s going to use that gun in the commission of a crime somewhere,” Suwannee County Sheriff Sam St. John said. “You’re going to have a higher probability of them taking that gun and either pawning it for some money or trading it to a drug dealer for the drugs that they’re abusing.

“You’re going to have (an even) higher probability of once they trade that gun in for drugs, for this drug dealer to use this gun in a commission of a crime.”

Thomasville Police Chief Troy Rich said the majority of Thomasville shootings are “drug dealer against drug dealer.”

Because many gun thefts and gun crimes are absorbed into the twisted web of the underground drug world, getting a clear picture of these crimes is difficult at times for law enforcement, Rich said.

Often, victims of crimes don’t want police to know of their drug activity, so they withhold key details to protect themselves or someone else.

Tracking Stolen Guns

When a gun is bought from a licensed dealer, two things happen: The gun is registered under the owner’s name and the serial number is recorded.

If that gun is stolen, the serial number is entered into the Georgia Crime Information Center, Dalton’s Jason Parker said. If recovered, the serial number identifies the gun and its owner.

The tracking problems arise when a gun is bought from a private seller. In those cases, the registration may not change and the serial number may not be recorded by the new owner.

“Any incidents where guns are stolen without the owners reporting the serial numbers aren’t entered into GCIC (Georgia Crime Information Center) because there’s nothing to track,” Parker said.

The chances of ever identifying and recovering such guns are slim to none, law-enforcement officials said.

“If someone breaks into your house and you don’t have the forethought of writing the serial number down off your guns, we’re going to write a report that doesn’t include that,” Sheriff St. John said.

“Finding that gun, unless it’s got some markings on it like an engraving, we won’t know it. I’m sure we’ve run guns that were stolen, but we can’t prove it because the owner doesn’t have the serial number. It happens more often than you would think. It happens too often.

“People buy guns and the last thing they think is going to happen is that it’s going to be stolen. We can find it if they bought it from a gun store or something, but if they acquired the guns from a private individual and we can’t find them, then there’s not much we can do.”

The Solution

Sheriff Paulk’s office in Lowndes County sits above hundreds of guns buried in concrete.

The story goes that Lowndes County used to seize guns through various investigations and then sell the guns to pawn shops. Because of the lack of security checks, the guns were ending up back in the hands of criminals.

So in the 1990s, when the addition that houses Paulk’s office was being built, a big hole was dug and about 300 guns were buried in concrete, never to see the light of day again.

Now processes are in place for pawn shops to identify stolen guns and to make sure other guns don’t end up with the wrong people.

But law-enforcement officials said criminals still get their hands on guns because people make it too easy to do so, especially by leaving a gun in an unlocked car or in plain sight.

“I can’t understand why people think it’s OK to leave a gun in their car at night,” Valdosta’s Chief Childress said.

Dunston advised people to take guns inside their homes or to at least lock them in a glove compartment.

He also warned about guns being sold at a low price.

“People may have all kinds of legitimate reasons to sell guns at a lower price than their actual value, but generally if a deal is too good to be true, it is too good to be true,” Dunston said.

Law enforcement also advised gun owners to fill out the proper paperwork when buying a gun so that it can be tracked if stolen and identified if recovered.

Childress said a key to lowering crimes of any type is interaction with the community and getting residents to communicate more frequently with law enforcement.

“Of course, your best deterrent to crime is the presence of law enforcement,” Paulk said. “That’s one of the things I’m doing now, is putting more people on the street.”

Some chiefs and sheriffs have said stricter sentencing for gun crime has become a good deterrent for criminals, but Baldwin County Sheriff Bill Massee said repeat offenders of violent crimes should serve even more prison time. Otherwise individual rehabilitation won’t take place and the criminal cycle will continue, he said.

“When they get out of prison, they change nothing in their lives. They continue purely in the criminal part of our society — either with drugs, gang involvement or thefts. Weapons are just part of their daily lives,” Massee said. “We don’t think when they are sentenced that the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles keeps them long enough, and we feel like it’s a revolving door. We keep arresting people with criminal histories.

“When you arrest a convicted felon for possession of a firearm, that immediately tells you that you’re working cases of people who already have committed crimes strong enough for them to be sentenced to the penitentiary in the state of Georgia.

“We’re simply looking at a continuation of crime. Evidently, the sentencing is either not strong enough to address the problem or society accepts it,” Massee said.

The SunLight Project team of journalists contributing to this report includes Charles Oliver, Billy Hobbs, Alan Mauldin, Patti Dozier and Thomas Lynn, along with the writers, team leader John Stephen and Eve Guevara. To contact the team, email sunlightproject@gaflnews.com.